Part of the Problem: Redlining

- Filed under "equality"

- Published Monday, March 16, 2020

- « back to articles

Much like the rest of our country, racism and racist practices were prevalent in law and social code in Iowa long before Iowa became a state. In 1838, Iowa adopted the territory of Michigan’s “An Act to Regulate Blacks and Mulattoes, and to Punish the Kidnapping of Such Persons,” a law that prohibited African Americans from settling in the territory without a court-confirmed certificate of freedom. The basic purpose of this law was to limit the number of runaway slaves and other African Americans from moving into the state.

Over time, Black Laws were passed prohibiting interracial marriage, voting or serving in the military by African Americans, or testimony against a white person in court by any person considered negro, mulatto, or Indian. Black persons could not be outdoors after dark and were limited from living in various communities; the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) gained strength in Iowa in the 1920s, including a parade through “Windsor Heights right down University” here in Des Moines.

In the mid-1930s, our nation was recovering from the Great Depression (1929 to 1938) which had robbed our population of economic and employment success, the newly-created Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) expanded the discriminatory practice, now known as redlining, to further prevent African American and other minority populations from obtaining home mortgages.

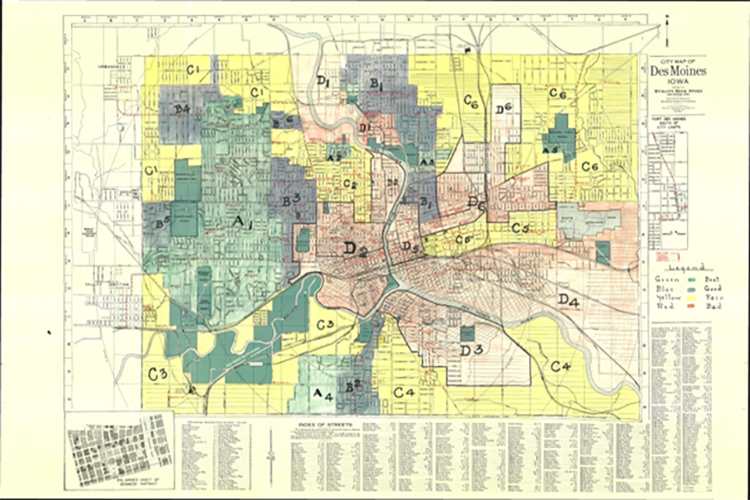

Redlining used a four-color coding system to define which areas should receive “good loans” for mortgages, and which should not be granted any loans at all. Red areas were marked as hazardous (predominately African American), yellow was marked as declining(still largely African American), blue was marked as desirable (homogeneous), andgreen was marked as best (whites only).

In this way, redlining was not only supported by the federal government, but it became the norm used for mortgage lending across the country. By the 1950s, as the government recognized that areas were becoming “blighted” ((low-income and African American neighborhoods), an Urban Renewal process was created to removed run down neighborhoods, move them to better and more modern areas, using new interstate systems to improve transportation.

In Des Moines, one of the largest Urban Renewal projects was the construction of I-235 through the center of the city. From 1957 to 1968, construction of I-235 displaced and destroyed substantial sections of the black community. Black businesses and venues were demolished (Center Street, Sherman Hill), leaving thousands without comparable housing or relocation compensation. In short, African Americans lost their modest homes and could not find affordable homes or were not allowed to move into specific communities throughout the city.

Although this is just a glimpse at the racial disparities in Des Moines and our nation, a considerable number of resources are available to learn more. The Urban Institute takes a deeper dive into how to talk about racial disparities. National Public Radio offers an interactive map on our history of discrimination. The Brookings Institution delves into the complexity of segregation.

For Chrysalis, redlining has strongly affected the availability of safe and affordable housing for women and families. Not only does discrimination affect quality of life, but research has proven that racial/ethnic disparities cause toxic stress, causing profound and negative consequences for physical and mental health – from generation to generation.

We hope you join us on March 3.